Colour is possibly the most misunderstood of all the subjects covered so far, and not an easy concept to simplify, but I’ll do my darndiddlyarndest to keep it simple.

I bet you think you know what colour is, but if you tried to explain green to a kettle, or blue to a cat, you’d struggle. And yet, when you create a colour image, your computer and your output device, be it monitor or printer, need to know what the colours are even though these devices are “blind”.

All colours, like anything else in computing, are assigned numerical values which are universally understood, by computers at least, so that when a computer receives images, they should look broadly the same as they did when they were created. As always in computing, there is a “however”.

Here it comes… However, when it comes to photos, not all colours are equal. A picture on one computer can have slightly (sometimes very noticeably) different colours on a different computer. This can be down to the set up of the computer, how the computer’s operating system handles colour, or more than likely it’ll be down to the monitor on which the image is displayed.

Think of the last time you went into a TV showroom. All those screens sitting side by side in the showroom, all displaying the same image – perhaps of Jeremy Clarkson’s face, or a baboon’s backside (ok, same thing), but have you ever noticed that every screen has a different colour cast? This is because each TV has a different setup, different software and hardware controlling and displaying colour. They’re not all “seeing” colour in the same way, so they each display colour differently.

So it is with computers, and especially monitors and printers. Each has their own idea of what red, green and blue are.

So if you need good control of colour for a corporate print or web project, how can you minimise the colour shift from one display to another? How can you control the colour output for a print project?

Part of the answer is colour profiles. Profiles are little files of information that can be invisibly attached to the photo, and whenever a computer opens that file it will see the information, read it and assign colour values accordingly.

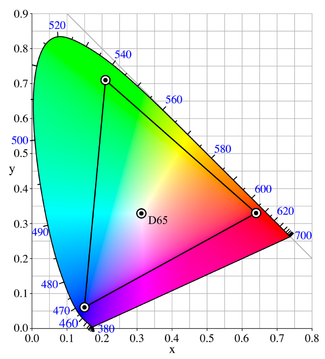

There are standard profiles you can use, and the two most common ones are sRGB and Adobe RGB (1998). As a rule of thumb, use sRGB for web display. It refers to a smaller range of colours (otherwise known as gamut), and since computer displays can’t display very broad colour gamut, this has become the standard colour profile for web use. For print, a good standard profile is Adobe RGB (1998) as this references a wider colour gamut that print output can take advantage of.

Using sRGB for web images at least gives you some hope that your images will display reasonably well on a range of different monitors.

Using Adobe RGB (1998) on print projects is a good start, but I would always advise you to liaise with the photographer and the printer before pressing the button on an expensive print run. Never send a job to print without getting proofs from the printer first. You may have to pay for proofs, but the cost of a wrecked print job will be far higher.

You also need to remember that profiles alone aren’t the whole story. Your monitor needs to be correctly calibrated if you want to adjust colour in photographs, and calibration is the subject of my next blog. I can feel the excitement mounting already!

I really have had to skim over this subject in a way that would have the experts spinning in their graves (if they were dead). So I’m including some links where you can get more information, and in the case of the ICC web site, possibly more information than would sit comfortably inside a single human head.

Cambridge Colour: http://tinyurl.com/dp6d9

A colour cube thingy: http://tinyurl.com/yg5g89f

ICC – heavy-duty information: http://tinyurl.com/6f8je5