Photography, like ventriloquism, has a slightly uneasy relationship with radio, but when I heard John Wilson was going to be interviewing Terry O’Neill (celebrity photographer), Don McCullin (war/conflict, now landscapes), Harry Benson (politics) and David Bailey (fashion) for Radio 4’s Front Row, I knew it was going to be a treat.

These four were chosen for their roles as a new wave of photographers who shot and helped shape the 1960s, although I found it slightly incongruous that they were being asked for their top tips on how more of us could get perfect “snaps.” And yet, this premise did illicit some interesting answers.

O’Neill, for example, apparently hates cameras, “I only have a little Leica and a Hasselblad,” he says. Is that ALL you have, Terry? I’ll dream on…

What was also interesting about O’Neill though is that he, like Don, never takes pictures at family events, and I have to sympathise there. Terry says it’s because when he takes a photo he wants the lighting and everything to be just right, and he’d hold everything up if he tried to take pictures at parties or on holiday.

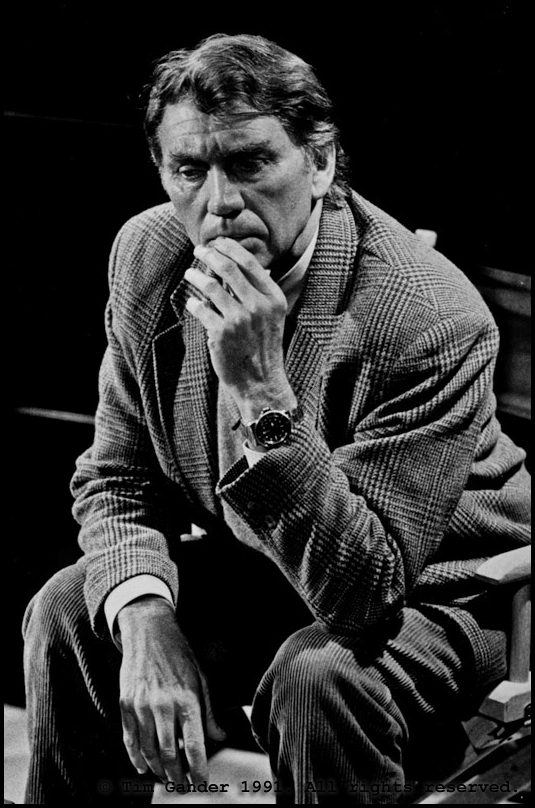

Like Terry O’Neill, Don McCullin also rarely takes any kind of family photo. His wife complains that he never takes pictures of her. His reason (excuse?) is that since his cameras have been used to photograph conflict, his gear is somehow contaminated, and he just wants to shut it all away in its cupboard until he needs it again. Of course at 76 years of age Don isn’t shooting conflict any more, but look at his Somerset landscapes and you’ll see the work of a man who is clearly at conflict with himself. Of the four photographers interviewed, it would seem Don is the one most haunted by what he’s witnessed.

Harry Benson made his name, rather like Terry O’Neill, photographing the likes of The Beatles, but where Terry majored in celebrity portraiture, Harry developed his career in politics. Among his most famous photos being the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy in 1968, and he talks about the experience of getting the shots (if that’s not too cruel a juxtaposition) of the presidential candidate as he lay dying, or already dead, in the arms of his wife. Harry says, “I didn’t even bother going to the hospital. I knew it was over. Anyway I felt I’d done my work for the night.” That was an incredibly telling line.

If you were to ask people on the street to name a famous photographer, David Bailey’s name would probably crop up most often. Famous for his style of fashion photography, where he moved the whole genre away from the static studio to the street, his approach has always seemed less reverential, and in interviews where he compares his career to the likes of Don McCullin, you can sense the relief he didn’t go to conflict zones to make his name. Maybe this explains why in this interview he delves back into his school days to find conflict and discomfort. Doesn’t seem to have done him any harm…

In terms of ‘tricks from the professionals’, Bailey does impart useful knowledge. Something I’ve seen photographers fail to do, and I’ve failed to do once or twice myself, is engage with the person you’re photographing. Talk to them, find out what makes them tick. You’ll always get a better portrait that way.

From Terry O’Neill we learn to always fill the frame with what you want to say. That’s a lesson I learned from my first picture editor, who used to scream FILL THE F*****G FRAME! at me (only for my first two assignments, after which I learned).

I like Don’s advice, that if you’re likely to get killed taking a picture, you better make damn sure the exposure is correct. He would leap up, take an exposure reading, then set and frame the pictures before pressing the shutter button. All this under heavy fire.

Harry’s advice, to always stay at the centre of the story for as long as possible, is also good advice. Not to get distracted by peripheral things.

Finally, David Bailey’s advice, apart from remembering to talk to your subject, is to shoot against a plain backdrop and shoot black and white. As he says, “With colour you look at the colour before you look at the message. With black and white you go straight to the message.” Of course shooting black and white isn’t a luxury we have for every assignment, but that quote is a useful one for making the distinction between colour and monochrome photography.

Don McCullin in typically down-beat mood during a presentation at the National Museum of Photography, Film and Television, circa 1991

Hear the full interview here, I highly recommend it.