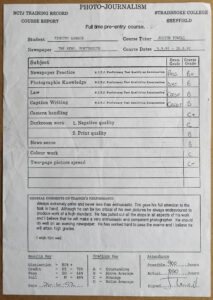

This is a blast from the past – my certificate in photo-journalism, awarded by the National Council for the Training of Journalists in 1992. It was amongst a stash of old school reports hoarded by my mum.

I don’t want to sound like an old man reminiscing, but this dates from an era when photographers were trained to take pictures for news. This no longer happens, and sadly reporters with iPhones are a poor substitute.

The course at Stradbroke College in Sheffield was, for a few decades, the only formal route into news photography in this country. You either took the one-year pre-entry course (as I did), or you could get a traineeship on a paper who would then send you on block release to cover the course over a period of a couple of years (I’m a bit sketchy on this as it was a long time ago!)

Having completed my full year, this certificate graded me on my progress at that stage. I then had to find a job with a paper (in my case, The Portsmouth News) and be indentured for two years before taking final exams, submitting a final project and qualifying as a senior photographer. Of course I passed with a Distinction, as you would expect.

But why is it a problem that this structure no longer exists? People consume news very differently today, so this training malarkey is old-hat and obsolete. Plus taking photos is so much easier; who needs training?

The issue arises because since newspapers have devalued their product to the point where most local papers consist of nothing more than a mixture of phone snaps, Google Streetview screen grabs or images lifted from Twitter, photographers no longer play the role they once did, that of first witnesses and documenters of breaking stories. We simply don’t have that anymore, at least not in the traditional titles.

We were also trained to cover events, even incidents, with professionalism and with a good grasp of press ethics and the law. In fact understanding the law as it related to our work was often useful in situations where those in authority (*ahem* the police) would try to obstruct our work. Today, many reporters and certainly members of the public don’t have the knowledge required to be effective image gatherers.

The cutting back of photo departments, which really got going in the early 2000s, also disposed of an incredibly valuable asset. While reporters were already being increasingly tied to their desks, writing stories almost entirely over the phone and without leaving the office, photographers were the main point of contact between the readers and their paper.

This wasn’t always an entirely comfortable role for photographers, but it had a value which is now lost for good.

It’s good to see the emergence of community newspapers now, such as The Bristol Cable, which work on a different business model to traditional newspapers, however they still haven’t fully embraced the power of photography, largely relying instead on their staff journalists or, at a stretch, casual freelancers. This is a shame because a publication will struggle to find its look and voice if there is no consistent style to its visuals. It also means there’s still no consistent contact between readers and editorial staff.

Of course I understand the issue of cost vs benefit, and most of these new news initiatives just don’t have the budget for properly-trained photographers, so they’re stuck with this new paradigm. They can’t cover stories consistently and in depth, so they fall short of the engagement they need to grow. For as long as they can’t grow readerships, they can’t invest in photography.

So while this certificate might be a flimsy document harking back to a time when the news industry was very different, it’s also a reminder that an entire industry, underpinned by structured training, has suffered a pretty mortal blow. I would love to see a new ‘traditional media’ emerge where photographers have regular patches and disciplines to cover (eg news, sports and features), and as platforms such a Twitter seem to be losing ground, maybe the time will come when people return to trusted, curated, edited and regulated sources for news.

There is hope yet! And then perhaps I can present my certificate and get a job on an evening newspaper.