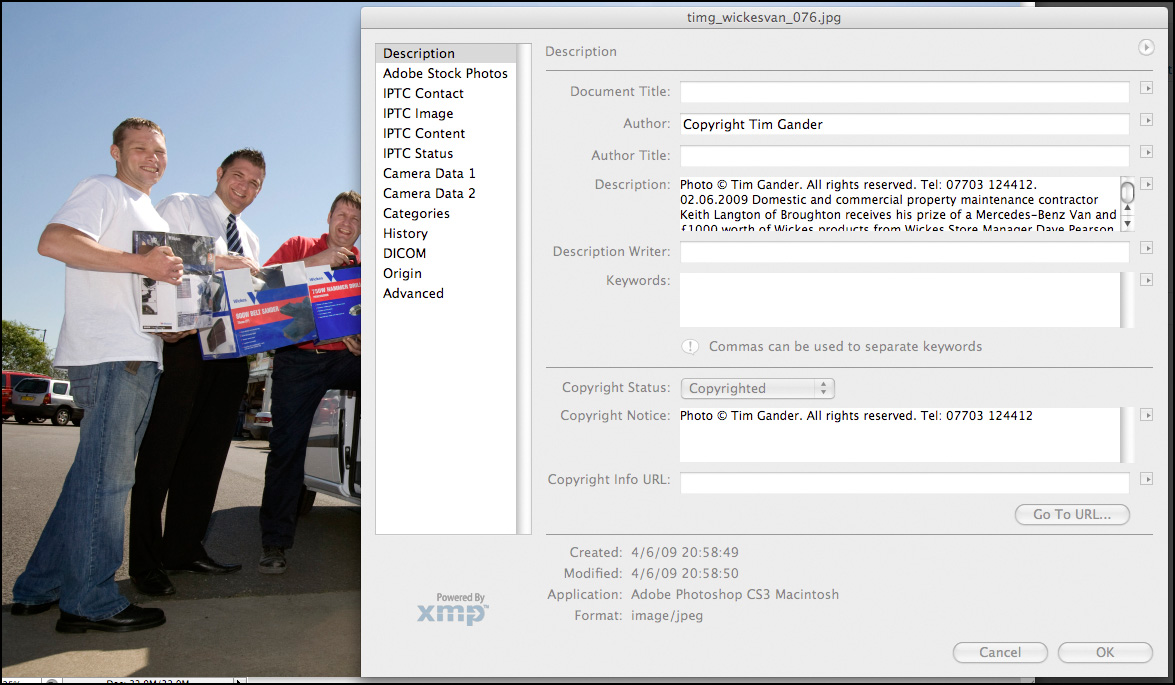

Following on from the previous article, where I explained that embedded captions in the photo’s IPTC file are an excellent idea if you want a news desk to be able to identify the subjects in your press release pictures, there is another very good reason to caption pictures fully and accurately.

You see when Google (other search engines are available – no, really they are) send their spiders to crawl your site, they can see the text and even understand it to some extent. But when they come across a jpeg image with no caption, Google just sees a blank space.

Think of it as describing the photo to a blind person. If you want Google to index your page and its contents, you need to tell it what’s in the photos.

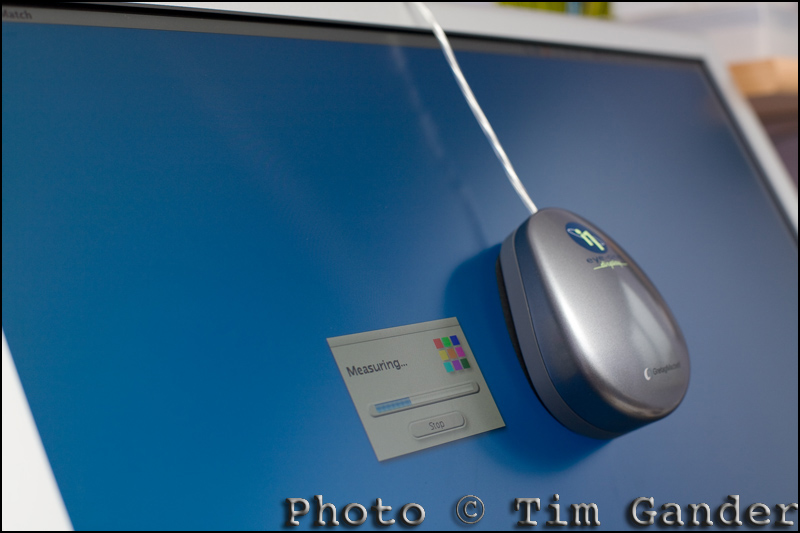

Search engines love photos, because they love content-rich sites, and pictures help with that. Search engines also want to know that the content of a site is relevant to the site itself, so again you can use captions to reinforce the content of your site. Google will love your site that little bit more if the pictures of furniture on your furniture restoration web site are described accurately, because the pictures and the written content will match up.

In addition to the caption describing the picture contents, you can use the Alternate Text field you see when uploading an image to a blog to give the spiders something else to latch onto.

If someone googles “queen anne table restoration” they’ll get search results on pictures as well as main web sites. If your site has properly captioned images, this can help draw visitors to your site. It’s another way of making it easier for search engines to find relevant content, so why not make use of it? It doesn’t cost anything but time.

One thing you need to be wary of if you don’t want all your caption time to be wasted is when using automated saving software, such as the Save for Web option in Photoshop because this strips out the IPTC data.

The Save for Web function is a throwback to the days of dialup internet connection, when IPTC data was seen as bandwidth-hungry and unnecessary. This is no longer an issue with broadband, but web designers use it as a quick way to deal with images. Unfortunately it causes problems, not only with captions and keywords being stripped out, but also with copyright information being discarded too, which can lead to legal problems which I’ll deal with in my next article.

So get writing those captions, give Google, Bing and um… whoever what they want. If you don’t feed the spiders good stuff, they’ll come after you!

So until my mummy washes and irons my superhero outfit, it’s time to say, UP! UP! AND AWAY!