The idea for this post was sparked by a post by fellow photographer and blogger Neil Turner, which you can check out here.

In it Neil discusses the requirement for professional photographers to fill in Risk Assessment and Method Statement (RAMS) forms when working for clients. As a professional, Neil is keen to emphasise that while RAMS and Health and Safety regulations do contribute to the freelancer’s work load, they are there to minimise risk and keep everyone safe.

But aside from how societal and commercial attitudes to risk have evolved in the past couple of decades, Neil’s post got me thinking about the riskiest job I’ve ever done. There are a number of contenders – scaling a 150ft hospital incineration chimney, or taking photos from the open door of a Royal Navy helicopter over The Solent having forgotten to attach my seatbelt (oops!), but these were back in the days when H&S didn’t seem so important.

My Riskiest Job

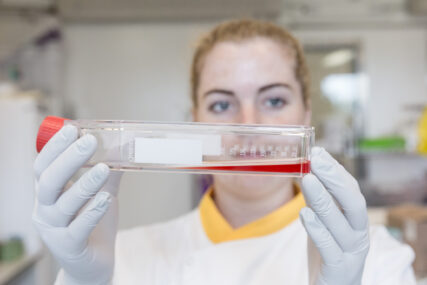

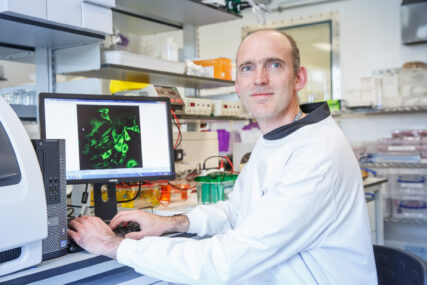

The job that I think entailed the most extraordinary risk mitigations was when I was commissioned to shoot some stock images for The Pirbright Institute and BBSRC. But the measures I had to undertake were less about my personal safety, more about bio-security. In this case, not accidentally transmitting a highly contagious pathogen to livestock.

Because I was going to be working in laboratories which investigate animal pathogens such as BSE, Bluetongue and, from memory, even Anthrax, the rule was that anything which went into the lab could only come back out either through a shower, sterilisation cupboard, or through a peroxide bath. This had certain implications on my approach to the task.

Kitting Up and Kitting Off

For a start, the kit I could take in would be very limited. I opted for my Canon 5D MKIII with 24-70mm f/2.8 L lens which would give me the best range of flexibility under the circumstances. There was no point taking a second lens in since the camera was going to be sealed into an underwater housing for the duration of the session, which was going to exit the lab through the peroxide bath. This also meant no flash because the underwater housing prevented this being an option.

All well and good for the kit, but what it meant for me and the client contact going in with me, was that not a single stitch of clothing could be taken in because it couldn’t then be taken out again.

This was the first and only time I’ve been naked in front of a client, but y’know we were pro’s. And so we stripped off, passed through a shower section, and dressed in scrubs on the lab-side of the biosecurity barrier. In this way, this laboratory is as sealed as it is possible to be from the outside world.

The Tricky Bit

Once in and dressed in lab scrubs, it was then a case of working out which parts of the lab would get the images the client needed, while also doing our best not to hamper the work of a very busy team of scientists. It’s also fair to say, as a working lab this was never going to look like a Getty Images photo session with clear benches, shelves of identical flasks and vials and clear white walls, all perfectly lit like Heaven’s waiting room.

I had to pick angles with the least distracting backgrounds and contend with a mix of off-white ceiling lights and a bit of window light here and there. Most of the colour correction was going to have to happen in post-production.

Add to this, working a camera inside an underwater housing is like trying to knit while wearing boxing gloves (not that I’ve tried that, but you get the picture). However, by the end of our time in the lab we had a good selection of images of all the key activities the client needed covering. So time to leave.

U-Bend If You Want To

This is where things got a little tricky. You see my camera needed to exit through the peroxide tank; imagine a sort of large u-bend filled with a powerful bleaching agent. We could have used the fumigation cupboard, but that would have taken around an hour and none of us saw an issue with passing the camera, in its underwater housing, through the peroxide.

That is until it got stuck in the u-bend. With a lab-side technician trying to prod the unit down with a rod while another technician outside the lab tried to hook it out (we’re talking a strong peroxide solution, so full gloves, masks and all the health and safety being observed), there was a 20-minute tussle to retrieve the camera.

In the meantime, my client and I got showered in the fanciest shower I’ve ever been in. A single-person cubicle with doors which locked automatically and didn’t release you until you’d showered for a set amount of time (six minutes, if memory serves).

By the time the camera equipment was retrieved and thoroughly rinsed off I was back in my usual clothes, but the underwater housing looked a little sad after its ordeal. Even one of the locking screws had sheared off in the process, but the bag was still watertight and everything inside was fine.

What’s Not In The Picture

I suppose what all this illustrates is how we can see a routine-looking image and not realise what’s gone into making it happen, a lot of which might be completely un-related to the photography itself. Sometimes this can be the extensive planning of logistics, other times health and safety considerations (often both), or even whether or not the photographer had to take their clothes off to do the job.

Needless to say, that last bit isn’t routine for me, and thankfully so for everyone’s sake.