Happy New Year! Let me kick off by wishing all my clients, past, present, and future a wonderful 2024 full of pleasant surprises.

Now we’ve had our fun and a bit too much chocolate, I’m kicking off the first blog post of 2024 by looking at some specific work I carried out between 2022 and 2023. Not for nostalgic reasons, but because it illustrates several aspects of my approach to various photographic tasks and challenges.

There’s a fair bit of ground to cover, so I’m dividing this into two posts. Make sure you’ve signed up to my blog if you don’t want to miss the second instalment!

This particular work was undertaken for the advanced propulsion R&I centre IAAPS (IAAPS for short) at Bristol and Bath Science Park near Bristol. I came to working with IAAPS through another client, University of Bath, which owns and part-funded the £70 million research facility.

Chances are you won’t have heard of IAAPS but in essence, it’s where vehicle propulsion research meets real-world implementation. Advances made here will find their way into internal combustion, hybrid, electric and hydrogen engines of the future. This could include propulsion fuels and methods not yet discovered!

What makes this a great case study for me is that my work for IAAPS has covered portraits, industrial, and event photography. The images have been used on the website, in press releases, and in printed promotional literature, because while IAAPS’ main function is automotive propulsion research, like any business it has to attract clients and investors to maintain its status in the top three research facilities of its kind in the world.

This requires marketing, which requires marketing materials. That’s where the photography comes in.

Let’s get into the photography then.

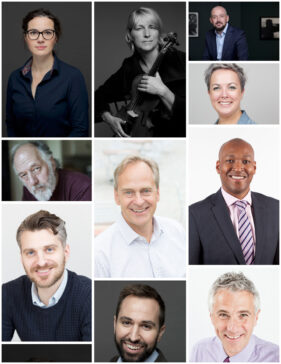

Portraits.

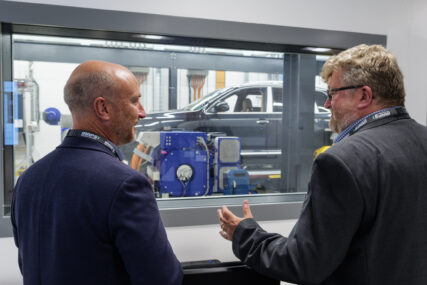

I won’t dwell on this aspect too much as I only had to do a handful of images of the Engineering Director and the Principal Engineer at a time when some creative editorial images were required for trade press and the website.

This was in 2022 when the facility, though substantially built, was still a building site. We were also still under COVID rules, so in I went, fully compliant with Health and Safety and COVID regulations.

Operating a camera while wearing a hard hat, goggles, gloves and a mask had its own challenges. The peak of the hard hat interfered with the flash trigger on top of my camera, while the mask caused my goggles to constantly steam up. Gloves don’t make operating the controls of a camera easy, but being fog-blind while trying to look through a viewfinder that isn’t up to your eye is “a bit awkward”.

Still, the session was short and these were hardly the biggest problems faced by humankind, so I was happy to fulfil the brief.

There was enough infrastructure already in place for me to use a backdrop which added some context, I just had to avoid including any dangling wires or ducts which hadn’t been finished and tidied away. In the event, a single softened flash on the subject and a second flash to clean up the backdrop gave me the results I needed.

Industrial.

More interesting in photographic technical terms was the industrial photography. In 2023, I was booked in to take pictures of completed test cells where the research and testing take place.

For much of this work, I was able to use a tripod which opened up new photographic possibilities.

With the camera “locked off” I could use the High Resolution (HR) mode of my cameras. While the pictures would be used mainly on the website, where super-high resolution is less important, I was thinking ahead to when the client might want to use the images on large printed displays such as pop-up banners.

In this mode, the camera takes 8 pictures of the same scene, shifting the image sensor in each of eight directions as it goes. This captures details which would otherwise fall between pixel sites on the sensor. The camera combines the eight images into a single high-resolution RAW file which is four times larger than the native image resolution of the camera. In short, I’m capturing a 96MB file instead of the standard 24MB one.

So if my client ever needs to blow the image up to fill an exhibition display, the resolution will hold up far better than if they’re trying to print from a regular file. To my knowledge, HR mode outstrips the resolution of any comparable camera on the market. It could be bettered by a medium-format camera, but then the cost of the shoot becomes somewhat prohibitive, and almost certainly overkill for the needs of my client.

This technique works best where both the camera and the scene are completely still. Since the camera is on a tripod, and nothing is moving in the test cells, it’s the perfect scenario for using HR.

Alongside the general views of the cells, I was also tasked with capturing details of the rigs, vehicles, sensors and other equipment. Often this involved hand-holding the camera, so HR mode wasn’t going to work because of the risk of movement between each of the eight frames being captured. Also, you can’t use flash in HR mode, and some of the equipment required additional illumination using my portable studio flashes to lift shadows or to add a touch of additional colour using gels.

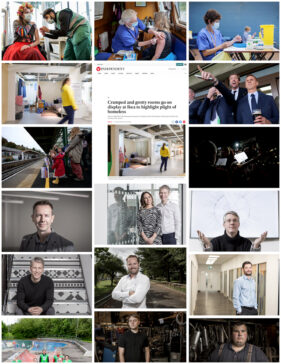

The gallery above shows a selection of the original images alongside screengrabs from the IAAPS site to show them in context.

These images are less likely to be blown up to create a full-bleed banner display, but high quality was still an obvious consideration when I took them, so of course I made sure I had one of my favourite lenses in my bag for this purpose.

One of the joys of the latest cameras (you may have heard the term “mirrorless”, which I won’t explain here) is that you can adapt older lenses to fit them. The Nikkor 55mm f/2.8 macro lens, launched in 1979, is designed for close-up photography. Indeed it’s considered by many as the benchmark by which all other close-up lenses are measured. I have no idea when mine was made, but they were in production for decades.

It’s also an excellent all-round lens for non-close-up work, being sharp and with no discernible distortion. It was perfect for the detail shots in the test cells where I was working at standard distances one minute, and extreme close-ups the next.

I decided to use this lens because I knew it covered everything I needed. I have more modern lenses with close-focusing abilities, but the Nikkor has the edge on overall quality. While it’s possible my client might not have detected the difference between images taken on one lens or another, I do believe in capturing the best-quality images I can.

What the old lens lacks is autofocus (or auto anything!) but manual focus just requires a little more care and concentration. It can slow you down, but that’s no bad thing as it also encourages more thought about composition.

Industrial photography can feel slow. You have to be hyper-aware of the details such as finger marks or dust on equipment as well as the usual considerations of lighting, composition and exposure, but I also enjoy the discipline this imposes.

There is no point rushing industrial pictures. It can take a considerable amount of preparation before even thinking about taking a picture, but my IAAPS client is happy to trust me to do what’s needed to get the best possible results. They’re dealing with high-end clients in an industry which is all about precision; being sloppy in the photography isn’t worth the risk.

While I know there will be additional trips to IAAPS for me in the coming year, I’ll welcome enquiries from anyone considering commissioning industrial photography for their promotional needs. Hopefully, this article gives a useful insight to my process.

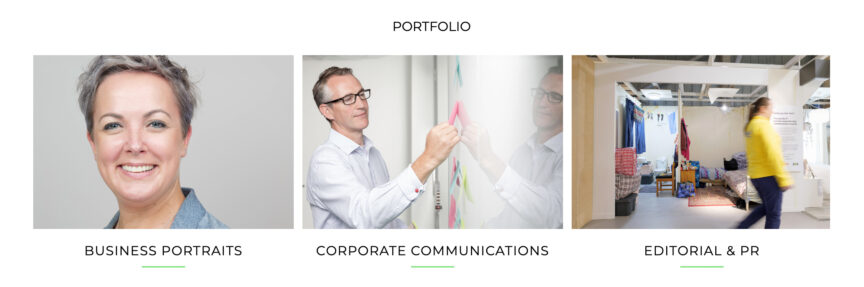

My portfolio is always evolving, so check it out here if you’d like to see more of my work.