A Welcome Comparison

The inspiration for this week’s blog comes courtesy of my good twitter friend Lau Merritt (@lau_merritt) who happened to mention she thought I looked rather like the late Mexican photographer Manuel Álvarez Bravo. I note two things in Lau’s comparison. Firstly that it is my looks and not my style which is reminiscent of the father of Mexican photography, and secondly that having been born in 1902 most portraits of the artist himself are of a much older man. I’ll not take it personally because if I have such an incredible face by the time I’m into my 80s I’ll be happy and when it comes to my work, I know I move in more prosaic circles. Besides which I know Lau well enough to know she only means it in the kindest sense.

I’m grateful that she mentioned this chap because I hadn’t come across Álvarez Bravo’s work before, and I’ve not had time to research it much beyond his official website, but I highly recommend a look and I’ll be seeking out more of his work in due course because it really is fascinating.

Álvarez Bravo’s archive stretches from the 1920s to as recently as the 1990s and what strikes me is how broad his themes are and yet how little they change over time. His work encompasses landscapes, still-life, portraits, nudes, photojournalism, portraiture, from the political to the fanciful, but always with a style which might remind you of Cartier-Bresson or Werner Bischof, but which is definitely his own voice.

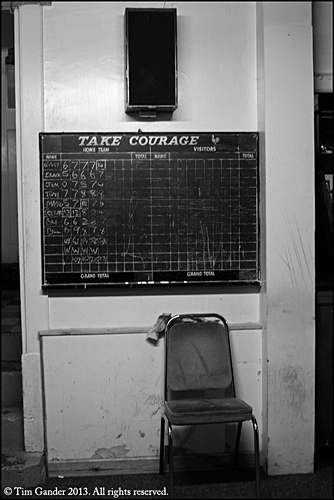

I’m not much cop at talking artsy fartsy stuff about photography, but I’ll happily share some impressions here. Álvarez Bravo’s work is of a very particular type; some simple studies of light and shape, the use of lines, shapes and motion to draw attention to whatever it is we’re meant to take note of in a photo and expansive landscapes designed to make us realise our own insignificance and mortality.

Like Bresson, Álvarez Bravo’s archive includes photos we would find difficult to take and distasteful in today’s society (see Boy Urinating, 1927 in the 1920’s archive). He deals a lot with death through depictions of the dead and the paraphernalia of death, even symbolic representations of death in the shape of subjects unrelated to death itself. His nudes rarely show the model’s face, also suggesting the the body as separate from the being and therefore subject to ageing and decay.

I’m really glad Lau brought my attention to Álvarez Bravo, and I’ll take any comparison as a compliment. In the meantime I’m going to have to get cracking if I want to leave such a powerful photographic legacy as his.

This post was a nice surprise. I’m glad that I made you discover the work of Manuel Álvarez Bravo. I hope more people get to know his work and those of other Mexican photographers. There are so many things I would like to say about his work, but maybe it would be better for me to write it on my own blog, instead of hijacking space here. Just two quick comments – interesting fact that despite his obsession with death, he lived to be a centennary!

As for the photo you mention of Boy Urinating, it is as controversial now as it was then – it was censored when it went on exhibition in 1929. In fact, he was quite an avant-garde artist for the Mexican society of his time. His nudes were quite unconventional/risqué, and that could have also been a reason for his models not to show their face.

Well, Lau, I couldn’t pass up the chance to take a look at this guy once you’d mentioned him and I was surprised by the span of his career. Last night I took a look in my copy of The Photo Book (Phaidon), and he has a page there too which I guess I’d not recalled from previous reading (there are hundreds of photographers in there). It talks about his career in cinema which I’d also not picked up from what I’d read about him. I wish I’d had more time to research him before writing the post, but then the post would have ended up being too long…

That’s interesting about the Boy Urinating, I just wonder if today he might have ended up being arrested for making indecent pictures of children. I confess I find that image difficult to view comfortably, but perhaps that’s the point. I hadn’t appreciated also the culture of the nude as it would have been in Mexico when he was making these images. It’s interesting that some of his models do show their faces and taken today might not be considered more than snapshots. It’s all about context. What did strike me about some of his nudes is how advanced from their time they were. The Good Reputation Sleeping (1938) image pre-dates some similarly-themed work of David Bailey’s by over 40 years.

I find looking at Álvarez Bravo’s work at once inspirational and depressing. I don’t think I could ever match his eye for the picture which says so much with so few elements.

Now I need to write my own blog about Manuel Álvarez Bravo. As you say, there’s so much to say. He’s the most famous Mexican photographer, but there are some as good or even better. And yes, they tend to have very crude images. Unfortunately, violence and death were a constant in the Revolution and post-revolution days and apparently it has started all over again.