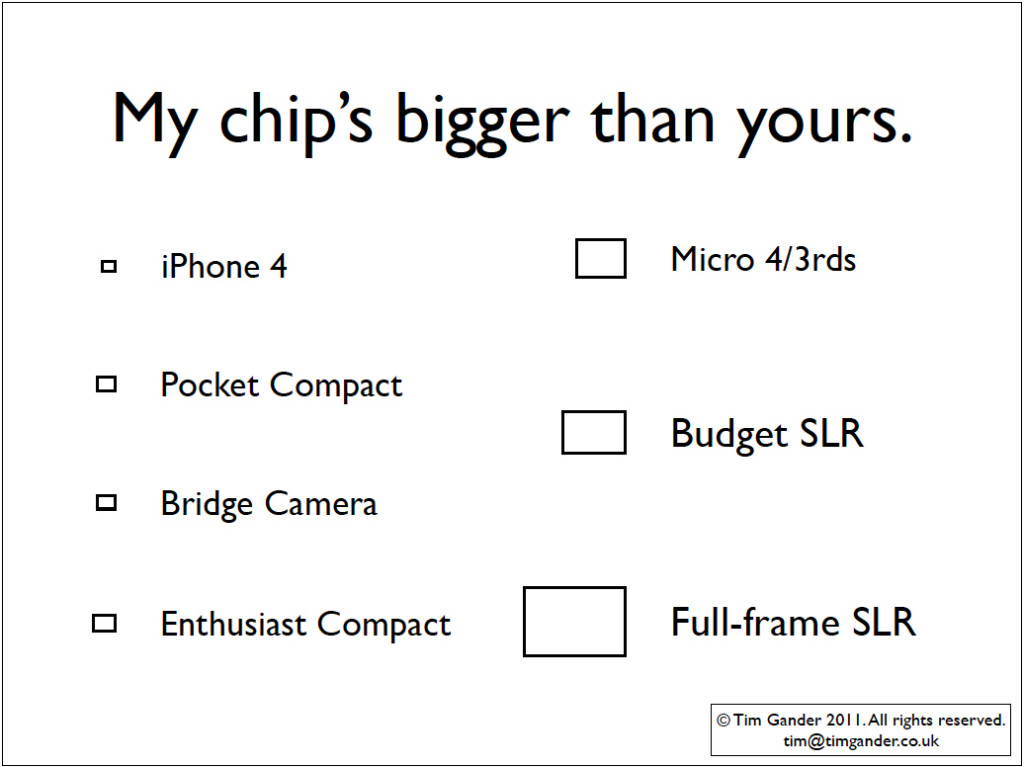

Here’s a slightly unusual scenario; A client requires one set of pictures for their website, and a couple more for press release. They only have one slot in which to get everything done, so who they gonna call?

Hilton Vending is a local business owned by Martin and Sarah Killian, set up in 1992 installing drinks and snacks machines. They recently ventured onto the internet and got their first website built, but they needed a few images to personalise it. After all, their clients know them and they’ve got a friendly approach so hiding behind stock images of anonymous people was leaving their website looking a little sterile.

At the same time, they needed images to go with a press release regarding the change that is coming to, er, change. To be precise, 5p and 10p coins will be changed to coins with a different alloy content and makeup (you can find out more here) and this will result in a cost implication for any business operating coin-based services – drink and snack machines, auto tolls like the new Severn Bridge crossing, parking machines. All these systems will need to be re-calibrated. Martin wanted to publicise this change with a press release, so needed a photo to go out with the story.

Luckily for Martin and Sarah, I was able not only to create a set of studio pictures for the website, but also illustrate the PR story with a suitable shot.

We spent a couple of hours trying different set-ups for the web photos, and in the end we got them some options which were suitable for use on various pages of the site. Originally Martin and Sarah thought they only needed a home page photo, but having got them to try various ideas we ended up with pictures they could use to spruce up the whole site.

Having got the studio shots done, I took Martin outside and worked on the idea of money being poured away as a result of the forthcoming coin change. I came up with the idea of Martin pouring coins out of a coffee cup to illustrate the waste, and the kind of industry that would be affected all in one shot. Oh, and I may have snuck the company name in the background too.

By combining the two shoots, Hilton Vending saved time and money, and got a few extra shots they hadn’t realised they needed. We were all ready for a coffee by the end.