Casual visitors to my website might be a bit confused if they read my blog. I’m supposed to be all Mr Corporate Headshot, Mr Corporate Comms and so on, yet my blog is often about my personal work.

Certainly SEO “experts” would have a thing or two to say about the fact that I’m not plugging the corporate work week-in, week-out, but I’m not sure they understand photography (or people), which in my view is a bit of a shortcoming.

Those experts will presumably have some understanding of search engine algorithms, but I’m more interested in posting material which allows potential clients a more three-dimensional view of my practice.

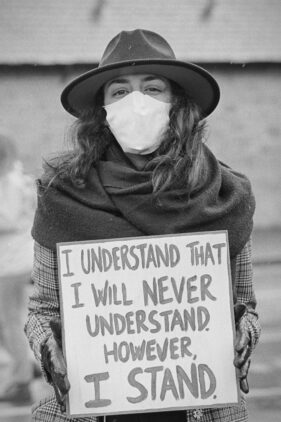

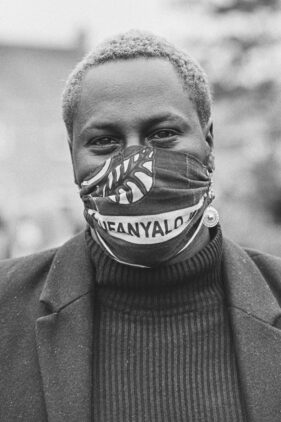

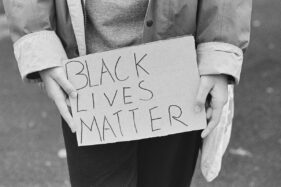

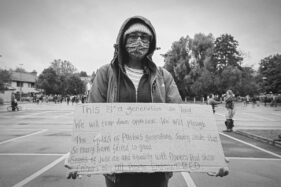

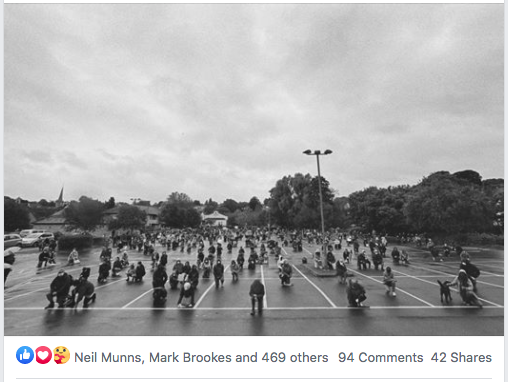

Which is why this week I am posting pictures from Salisbury Plain*, my current personal project.

After months of barely leaving the house, I was so pleased to be able to get back on the project and I’m happy to share a few of the latest results with you. Some, if not all of these, will be made available as fine art prints via my takeagander website where you can see more images from this project which I made before lockdown.

But given that this blog often veers away from the pure business of corporate communications work, how does a project like this help potential clients choose me over the next photographer? Why do I post personal work here? Let’s turn that around and ask, “What kind of photographer would I be if I didn’t do personal projects?”

Go to a dozen photographer websites and the majority will tell you at some point just how passionate they are about photography. All too often this doesn’t show through their work. I believe they are passionate about being a photographer, but mostly because they like having, or being seen with, cameras. There’s a chasm of distinction between being genuinely passionate about photography, and liking taking pictures (or liking owning nice camera gear).

My personal work is mostly shot on film using a variety of relatively low-tech, often un-glamorous cameras, because photography is the important part to me, not owning the gear or being seen to have the latest equipment. Working this way is also part of my “keep fit” regime in that it keeps my photographic eye honed even during quieter periods (lockdown being an extreme example).

In a world where “everyone’s a photographer” my passion isn’t just about being a photographer, it extends to the purpose of photography, its purpose and value to society. Getting heavy now, huh? Sorry, that’s really a whole other blog post there.

Perhaps next time you’re looking to book a photographer other than myself for a job (yes, I do know this happens!), take a look to see what personal projects they’re working on. If there are none, ask yourself if they’re genuinely as passionate as they say they are.

*I haven’t yet settled on a permanent title. I’m passionate about finding a good one.